By Alison Laurio

In 2022, before the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, a leak came out that it was about to happen. This prompted some states to begin changing abortion laws to limit or ban access to the procedure, and also developing laws to prevent social workers from working with youth seeking or going through gender-affirming care.

“What do we do when it’s in our ethics and we’re told we can’t do ethical practice?” said Valerie Arendt, executive director of NASW’s North Carolina Chapter.

When planning for the chapter’s annual conference began, Arendt said they were thinking, “What happens when our ethics and the law collide?”

The written promotion for the one-time program they developed states:

“Social work history is filled with instances where social workers have had to make decisions of conscience about whether to obey the law, particularly when doing so seems to conflict with social work values. These are the dilemmas that generate intense disagreement among practitioners, dilemmas that require earnest collegial consultation and supervision, and reflection on the implications of the National Association of Social Workers Code of Ethics. This conference will dive into the Ethics of Resistance: ‘When social workers get into Good Trouble.’”

Arendt believes those who signed up for the March 17 program “walked away with a better understanding of our profession’s history — both good and bad.”

Good Trouble

Lee Westgate, MBA, MSW, LCSW-C, adjunct professor at the University of Maryland School of Social Work in Baltimore, shared some of the words from his program message.

“In preparing for the keynote I delivered to NASW-North Carolina, I thought deeply about the urgency of this moment and the overlapping human rights crises that are seemingly ubiquitous in the world around us. We are all bearing witness to a coordinated effort to weaponize the structure of the legal and cultural systems to crush the real power of everyday people — and especially historically marginalized people and populations.”

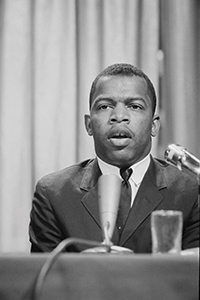

“Civil Rights hero John R. Lewis (pictured, left) said it much more eloquently than I ever could,” Westgate said.

“‘Speak up, speak out, get in the way. Get in good trouble, necessary trouble, and help redeem the soul of America.’ His eloquent framing of good trouble was and remains a call to action for all of us to use our voice and our power to preserve our own humanity and to protect the rights and freedoms of one another.And his call to action, also like the civil rights movement, underscores the importance and place of civil disobedience.”

“Our Code of Ethics demands that we as social workers not be complicit in systems of harm and that we act on behalf of our most vulnerable neighbors and combat oppression where it exists,” Westgate said.

“There have been times when our Code tracks with the legal law of the land, and even with the cultural mores and norms of the land, and this is a moment where the incongruence between ethics and legal law could not be more apparent.”

Outlining the substance of what is transpiring today necessitates that we take a long view on the march toward the urgency of this moment, he said.

“And really from a historical context, you cannot adequately explore the topic of good trouble without recognizing the theme and reality of the violence that is intrinsically linked to the colonization of this country.”

“It is essential that we as social workers especially recognize that oppression was baked into the conquering of this land and that violence enabled the perpetuation of white supremacy,” he said.

“This perpetual wielding of power and dominance looks like the displacement and genocide of tribal nations and the sanctioning of the chattel of slavery over the course of centuries.”

With his keynote, Westgate said he sought to thread the connection between those historical chapters and how they collectively facilitated the structure of our current socio-political reality.

“In essence, what we are witnessing today is an extension of unchecked historical violence. And we will not be able to move the needle when it comes to matters of social justice until there is recognition of these truths and the concerted effort to disentangle ourselves and our profession from all of the ways that we have become complicit in harm — especially through our own silence.”

Westgate said the overarching message of his presentation underscores the relevancy of this moment for social workers.

“We live and exist and serve in this context. Not only are we facing a crucible moment in our shared history, but we are also facing the immobilizing force and impact of fear. That fear permeates because of the divisive nature of these human rights attacks. For those of us that are minorities and are denied equal access to power, the fear and isolation in this moment are very real.”

As social workers, we must endeavor to know and uphold that an attack on one is an attack on all, Westgate said.

“We are connected to one another, and allowing the passage of laws that infringe upon the human rights of one group sets a precedent for the collapse of freedoms for others.”

History Lives

Past historians researchedand wrote social work history and policy, but that has waned for about the last 30 years, said Justin Harty, PhD, MSW, LCSW, assistant professor at the Arizona State University School of Social Work, who also spoke at the NASW-North Carolina conference. Harty said there have been at least eight key historical periods, some clearly divisive times, and “the profession of social work had roles in all of it, good and bad.”

The profession was able to resist and hide itself from past atrocities, but finding itself currently in a politically divisive time “is nothing new,” he said.

“When social workers were in the reconstruction era, it was not technically a profession yet,” he said. “So, many communities of color leveraged long-standing traditions of self-help and mutual aid during the history of becoming free people. If you look at the act of social work, self-help and mutual aid, you can definitely draw a distinction.”

Social work texts skip over the reconstruction era, Harty said. In the history of the profession, there were charity organization societies in the 1920s, notably Jane Addams and her work, for one.

But, he said, “We omit the flaws.”

One of the reasons Black social workers were upset in 1968 and created the National Association of Black Social Workers was the reflection of repression, Harty said.

“For sure, we do a lot of great things, but the profession also has created a lot of harm. When we fail to acknowledge our history, to me that is the part I find most troubling.”